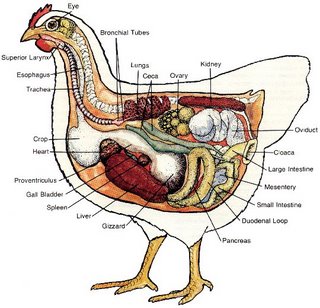

You don't have to frown or show repulse. After all, where did these eggs you ate at breakfast came through? Answer: the distal portion of the hen's digestive and genital tract, the cloaca where egg shells were in close contact with fecal material, loaded with salmonella, campylobacter and other pathogens.

You don't have to frown or show repulse. After all, where did these eggs you ate at breakfast came through? Answer: the distal portion of the hen's digestive and genital tract, the cloaca where egg shells were in close contact with fecal material, loaded with salmonella, campylobacter and other pathogens.In some places, there are stores specialized in tripe, a generic term applied to any part of the stomach and intestine. Still, I don't think it will be easy to find the distal portion of bovine intestine - in Southern Peru sometimes they are called "culata", an euphemism, since that word means the handle of a gun. Let's assume you can get some. First, clean it carefully, to remove any remnant of E. coli. Then cut it in open and slice in segments of about three inches. Boil them for two hours and drain. Season with red chili, gar

lic, cummin, salt and pepper. Fry, turning and making sure both sides are brown. Serve with boiled potatoes and onion rings marinated in oil and vinegar.

lic, cummin, salt and pepper. Fry, turning and making sure both sides are brown. Serve with boiled potatoes and onion rings marinated in oil and vinegar.I must confess that I have never prepared, or even eaten this dish. Then, why I am recommending it? Because I have enjoyed very similar dishes in popular restaurants, "picanterias", specialized in spicy ethnic food.

From my perspective, a cook has to be really inexperienced and/or dumb to make a bad meal out of a piece of tender meat, and other expensive ingredients (think of trufles, heavy cream, shrimp, cognac). But a cook has to master his art to turn body parts usually discarded (blood, tripe and other entrails such as the heart, animal skin) into tasty dishes. That is what former slaves and the rural poor, forced by neccesity, did in Peru. I take my hat off for them!